I have to confess to loving an almanac! Any almanac. Complex diagrams, instructions, prophecies. A nicely organised year set out for you to take away some of the uncertainty of the unknown future, very neatly put here by Bernard Faure…

A calendar ….implies a domestication of time, as response to the anxiety caused by the constant flux of nature and things, By fragmenting time into increasingly small units it reassures people.

Bernard Faure in a review of Marc Kalinowski’s Divination et société dans la Chine médiévale here

Almanacs were incredibly popular throughout the world for centuries and to some extent still are. My next post looks at the beginnings of movable type in China but it is interesting that Gutenberg printed almanacs before his famous Bible, so much was the demand and the profit! And as we are coming up to Chinese New Year this seemed an appropriate choice.

A Chinese Almanac Fragment from AD 877

This is possibly my last printing experiment based on the manuscripts found in Dunhuang and it’s from a wonderful almanac fragment, an intensely complex document, 29 cm high and in its entirety 115.5 cm long.

It would have been cut into separate blocks of wood and printed simply by inking, possibly with pads, and then pressing paper onto the surface and rubbing from the back.

British Library Or.8210/P.6

woodblock print on paper

You can see enlarged sections of the scroll at the International Dunhuang Project here

This beautiful scroll is split into sections which include zodiac animals, lucky and unlucky days, fengshui diagrams, charms and amulets.

Many Chinese households will regularly consult an almanac (or calendar) based on the lunar year that provides a set of guidelines to promote or advise against certain tasks or events being undertaken on certain days. Claims for the origins of this book go back over 4200 years to 2256 BC, from which date it is said to have been in constant publication. Originally produced solely by the imperial palace whose supposed link to the Heavens offered the ultimate authority on all matters celestial, the almanac is now freely published, but a certain ritual still surrounds its use. In its handling, clean hands and a degree of reverence are required. Old almanacs must be disposed of by burning, either at a temple or with care by each family, in order to release their powers back to Heaven and the almanac must always be stored with respect and never placed on the floor or beneath a table. Despite the lighthearted treatment of astrological suppositions surrounding the zodiac, the respect afforded to the almanac reveals the ongoing belief afforded to the more complex arts of astronomy and divination and their importance in Chinese society.

From an overview of the role of the Chinese Almanac, published by the Dunhuang project here

Detail of the zodiac figures from right to left: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit (or hare), dragon, snake, horse, sheep (or goat), monkey, rooster, dog and pig (BL Stein Collection Or.8210/P.6) International Dunhuang Project website

I am very fond of the lively cutting style of the animals particularly the little snake simplified to an arrangement of geometric shapes.

Almanac Censorship

An important side issue is who controlled the printing of almanacs. In China the State tried to restrict the information the public received by only allowing state approved almanacs to be printed but often local printers would risk prosecution and make their own, so high was the demand and the profit.

Under the Censor’s Eye: Printed Almanacs and censorship in ninth Century China is a PDF written by expert on the silk road artifacts Susan Whitfield. If you have time to read this, it will explain everything! https://www.bl.uk/eblj/1998articles/pdf/article2.pdf

Susan is Professor in Silk Road Studies, Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures and the University of East Anglia. Author of many books and articles… I have two of her books now 🙂

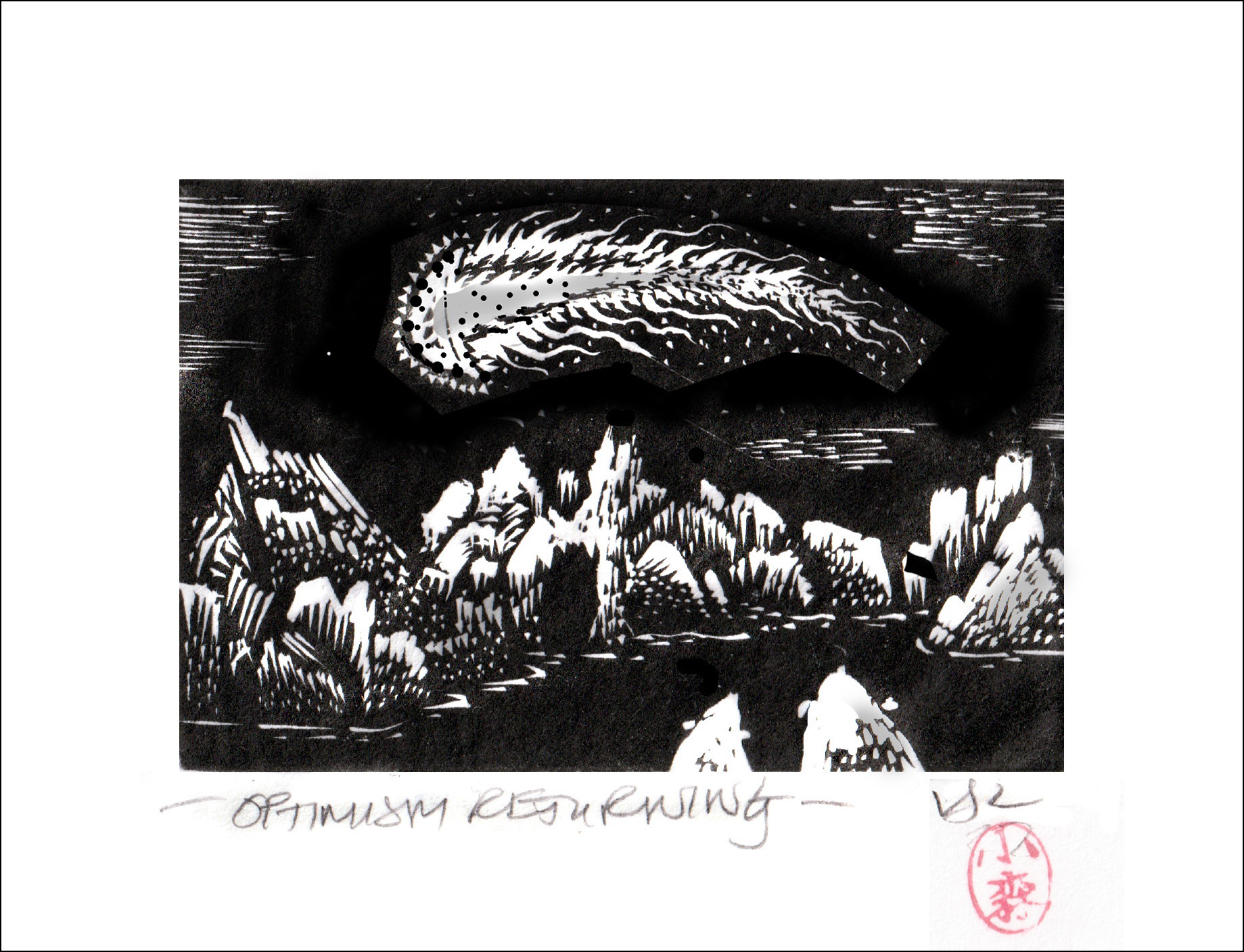

The Images

I had a very hard time deciding what to choose from this fabulous piece, and looked at a few images; the creature at the base of the scroll, the zodiac animals and these very strange figures situated further to the left of the zodiac animals.

But what are they? It has taken me 3 weeks and some extensive research including contacting Silk Road expert Susan Whitfield who I mentioned above. So I am very grateful to learn via her and her colleague that they are 5 demons or ghosts associated with illnesses.

After a bit more digging I find that if you were suffering from an illness on a particular day it could be linked to a certain demon. For a cure you would need an “talisman” or written charm to dispel the malaise brought on by this unwelcome being.

Activating the charm entails either ingesting the charm, (first burnt and the ashes mixed with wine) or pinning it to the door to ensure the disease carrying demon would not enter the house.

These things are useful to know especially at the moment.

![]()

Almanac Animal and Tigers

Eventually, not wishing to inadvertently whistle up some demonic presence, I chose the little creature featured as the largest image on the scroll. Boar or Ox?

I made a small reduction print in two colours. A simple enough exercise but it does involve some registration which is always an issue for me!

Block and stage prints

The Almanac Animal.. 10.5 x 8.5 cms printed on Chinese paper (you can see the original stamp on the paper at the top right)

New Year Tigers

Then, because the coming week welcomes in the Chinese New Year I looked again at the zodiac animals.

The tiger in the Dunhuang Almanac looks rather like a small domestic cat but I did want to celebrate this welcome new year so I turned to early Chinese stone rubbings.

The earliest known rubbings date from some 200 years before the almanac and were created by pressing damp paper over carved stone texts or images and then inking the paper surface. ( You can find lots of information and beautiful images from the Field Museum here )

The effect will also happen when printing woodcuts onto thin papers using a baren. The image will appear on the back, a technique used by some artists use to create soft, textured print images.

So I cut a block with my adaptations of an early Chinese “feline” image. I much prefer the original …mine are just much too cuddly.

To replicate a traditional way of printing I inked the block with black sumi ink and printed the image with a baren on a thin natural coloured Chinese paper and stenciled in some spots in lucky red.

Two tigers: image 16 x 28 cms printed on natural coloured Chinese paper

The image showing through on the back of the sheet after printing

Block and prints

I also made a few other prints to practice my registration technique…. I will improve!

Some traditional red and green…

Some more variations, including two printed in jade on a gorgeous Chinese “dragon cloud” paper. A fine silky paper with fibers and flecks of gold leaf.

The paper is very translucent, my hand shows slightly dark behind the paper.

And finally a mix of green, red and dark grey…

New Year Tigers. 3 colour woodcut 16 x 28 cms on Chinese rice paper

Happy Chinese New Year!