Today, instead of researching more about herbaria which was my intention, I became completely engrossed in the lives of the plant hunters. My admiration for them grows in leaps and bounds. I have been reading amongst others a small paperback “The Plant Hunters” by Tyler Whittle which is full of very entertaining information about these extraordinary people. From the diminutive Albertus Magnus, 1193-1280, who walked all over northern Europe, dissuaded the Poles from eating each other and collected an extraordinary number of plants into the bargain, to the pirate plant collector William Dampier whose terrible cruelty earned him a court martial and who was the unlikely inspiration for Coleridge’s “Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner”. I was really just looking for how they transported the plants but got horribly side tracked for hours .. and hours..

However the problem of shipping live plants was of course a real headache for the early explorers. I can barely get a few leaves back from Leu without them withering to nothing, let alone a 3 month sea voyage. Many ways of shipping were tried, packing things in barrels, and wrapping them in oil cloths, suspending delicate things in nets from cabins roofs, and making elaborate sets of boxes within boxes but things could happen on a voyage, storm, shipwreck, mutiny ( as on the Bounty whose revolting crew threw the precious cargo of breadfruit overboard), the neglect of the crew, salt water damage, excessive heat, excessive cold and too much or too little light etc etc etc. Pests on board were a problem too. John Bartram sent boxes of new and precious plants from America to William Collinson in the UK and on one occasion a rat’s nest complete with young was found “amidst the ruin of plants and dead greenery”. Seeds were also sent but they were as tricky to keep in good condition as live plants. Dried plants were useful for identification and if the expedition could afford it an artist went along, but even drawings were subject to the same hazards.

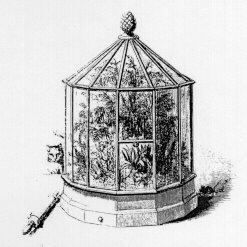

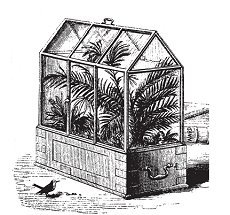

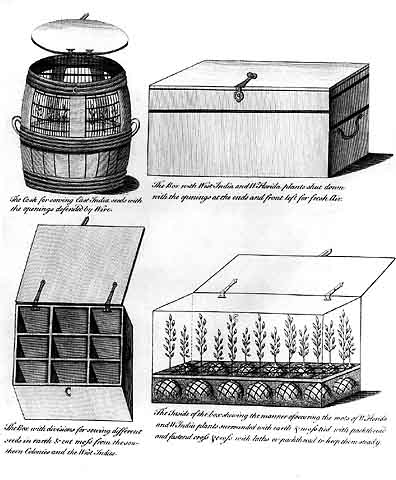

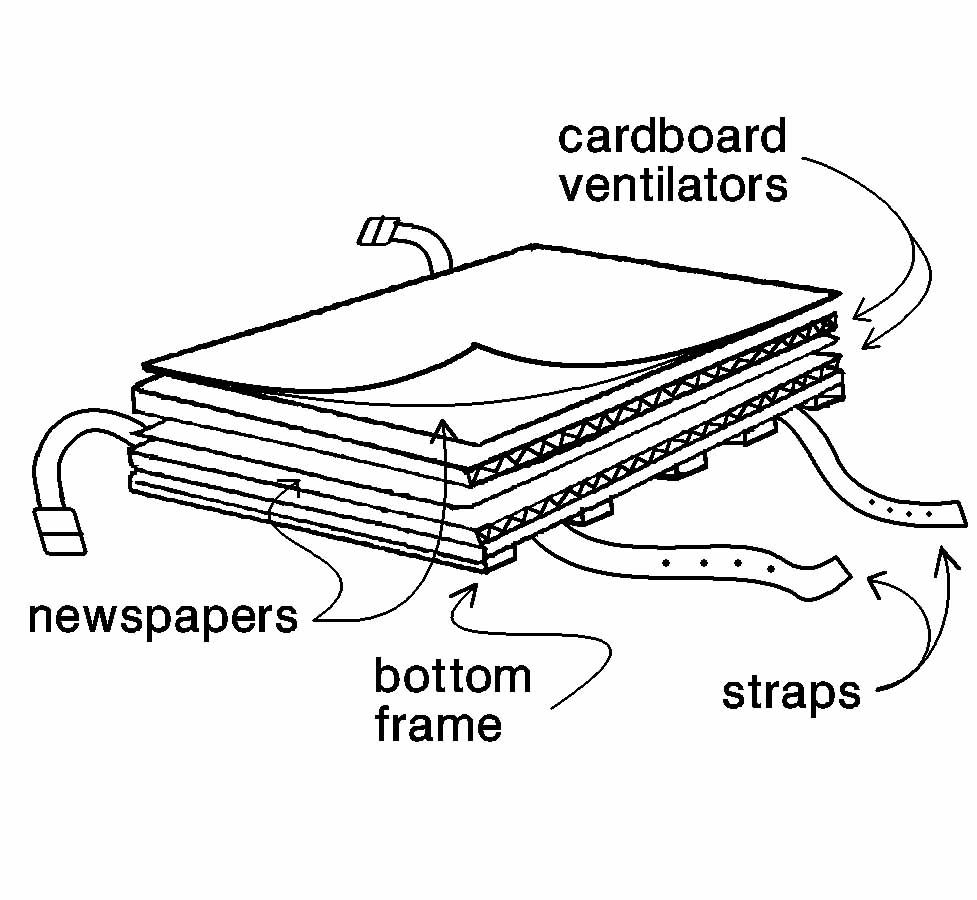

Some early plant carrying boxes

The big change occurred with Dr Nathanial Ward’s accidental invention of the Wardian Case in 1829, which made transporting plants more successful, so much so that plant distribution, especially economically important plants, around the world would change.

Dr Ward had an interest in entomology and ferns but lived in a very polluted part of the docklands in industrial London, and neither the ferns nor the butterflies thrived. However he was aware of the importance of clean pure air for the survival of natural things and in his own words,

“I had buried the chrysalis of a sphinx [moth] in some moist mould contained in a wide-mouthed glass bottle, covered with a lid. In watching the bottle from day to day, I observed that the moisture which, during the heat of the day arose from the mould, condensed on the surface of the glass, and returned whence it came; thus keeping the earth always in some degree of humidity. About a week prior to the final change of the insect, a seedling fern and a grass made their appearance on the surface of the mould”

His curiosity for how long the ferns could survive in this sheltered environment (in fact for 4 years until the lid began to rust), led to the hugely important botanic/economic discovery the Wardian Case.

The success of the cases wasn’t just the fact that they were made from glass but that they were sealed and not disturbed, providing the plants with a stable climate in which to travel. If you have ever had a terrarium you will know how delicate the micro climate inside can be.

Photo of a replica Wardian Case from the National Maritime Museum here

Ward was determined to test his cases well though and so on his orders two cases were stocked with native plants in Australia. These already proven “bad travellers” were put aboard a clipper and sent to England.

” Stocked with Plants notorious for their tenderness and their reluctance to leave their natural habitat they were sent on the long storm wracked voyage round the Horn. Between Botany Bay and the Pool of London the plants were subjected to variations of temperature from 20 to 120 degrees. They were rolled sideways and tossed backwards and forwards on the swell and roll of two oceans. But at the end of it all when Dr Ward went down to the quayside and opened his cases he found the plants secure, fresh and green and full of promise. His confidence in the cases was entirely vindicated”

Exerpt from the “Plant Hunters”by Tyler Whittle

The new Wardian cases in which seedlings could be planted and transported enabled Robert Fortune, who I wrote about before in regards to tea, to transport the 20,000 smuggled tea seedlings from China to Assam, to start India’s tea industry. Rubber tree seedlings, after germination in the heated glasshouses of Kew, were shipped successfully in Wardian cases to Ceylon and Malaysia to start the rubber plantations and Joseph Hooker was able to ship many new and different specimens back to Britain from his four year Antarctic voyage.

A Wardian case from Kew gardens. see here ” The Wardian Case being filled in the photograph remained in use at Kew until the 1960s when air transport and other means superseded it.

Below are two examples of the decorative Wardian cases which I particularly like for the inclusion of the cat and bird looking on, perhaps a little nonplussed at being shut out of their normal haunts.

….More on pressing plants

There is so much information on the web re pressing / preserving flowers and I am sure that many had or still have old flower presses, or like me, just make do, but an easy plant press and proper collecting instructions can be seen here from Fort Hays State university

And there is a nice PDF on how to make a pressed specimen from The Fairchild Gardens with a sample of the correct label here.

If I had time I could get very involved in developing and keeping a herbarium but I will save this delightful pastime for when I get my dream garden.

Its Saturday ………..