Weekly Woodcut No 10

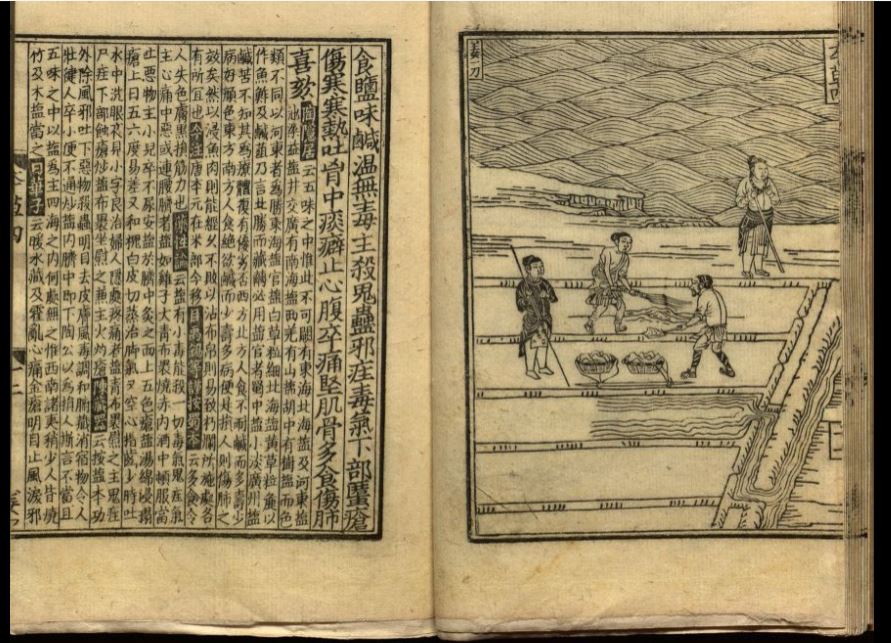

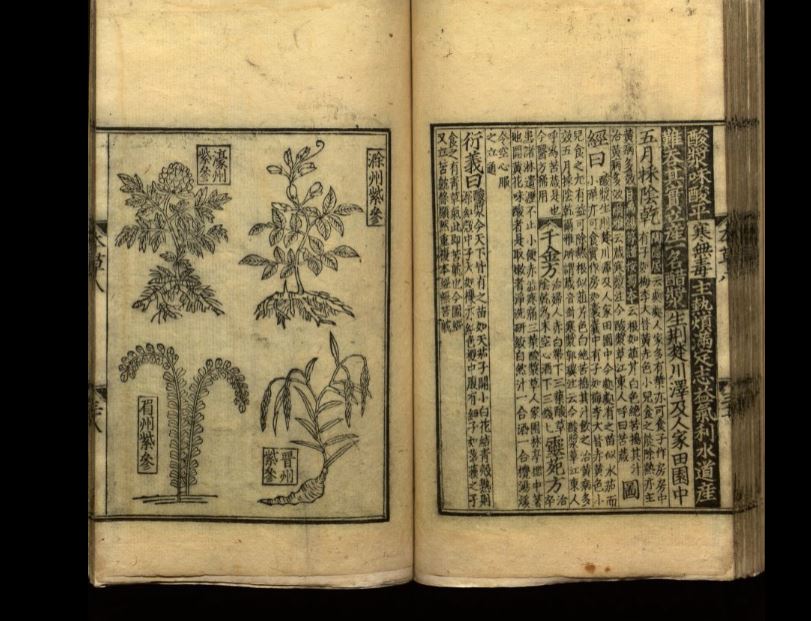

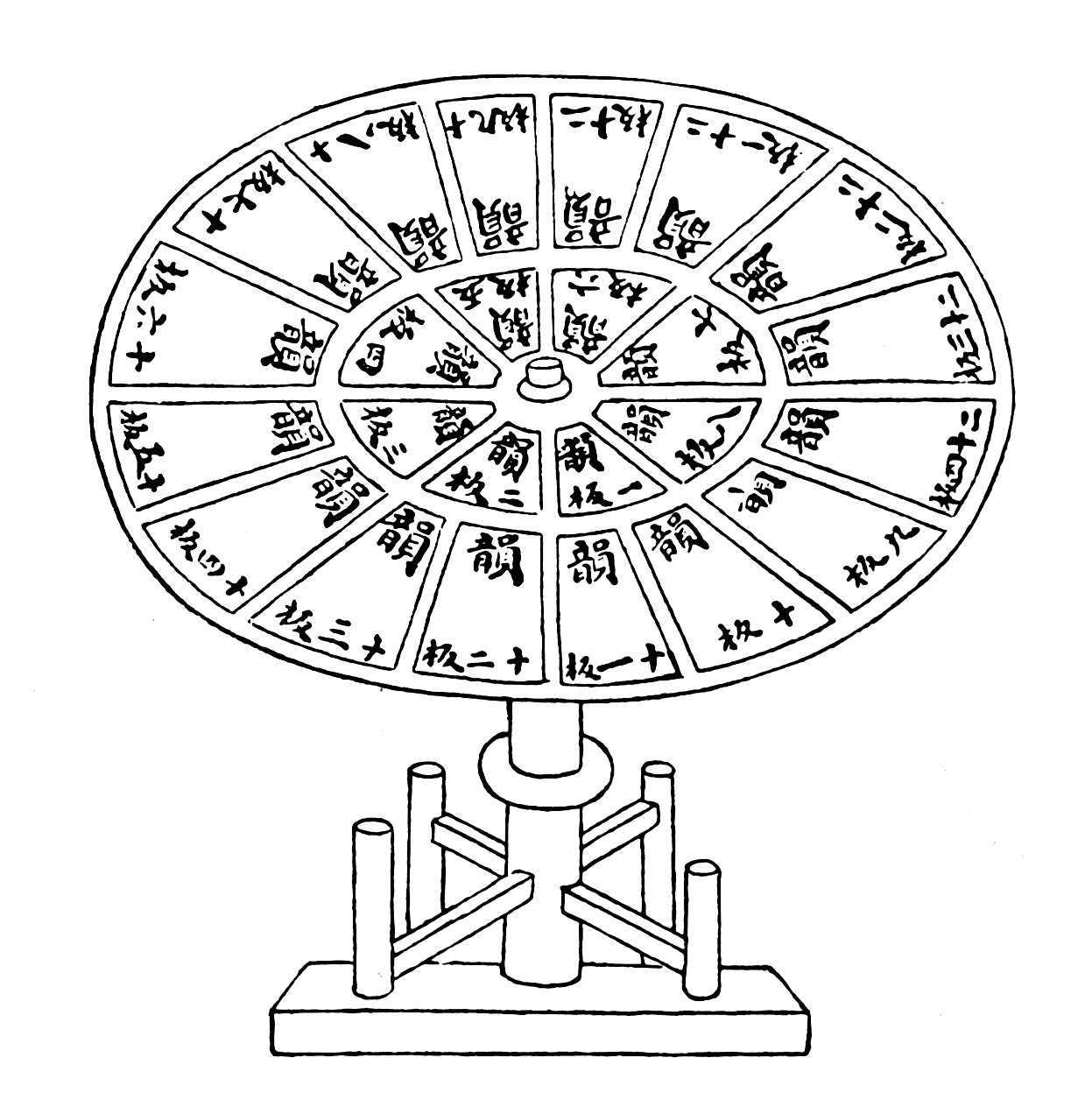

This week I am starting to look at the extraordinary 15th Century when the use of movable type developed. Printed words became accessible to many, bringing with them knowledge, ideas, images, stories and a fair bit of fake news. It’s the world of the “Incunables” fabulous printed and illustrated books on every subject you can imagine.

But just before books with movable type, woodblocks were produced for making into small booklets and prints usually for devotional use. There are many questions to ask about the who and the why and some interesting issues around who exactly was allowed to make the prints. Copyright as now, was an issue for the painters guilds who objected to carvers making images based on their paintings, but in the monasteries protected from prosecution it was natural that the monks, already skilled craftsmen would turn their hand to woodcuts. These were mostly images of saints for sale to visitors and pilgrims, a nice little earner to swell the coffers.

There are many things that need considering when looking at work of this time, whether things were printed on paper or parchment, were made from woodblocks or hand illuminated or a mixture of several techniques. It’s a time of change and innovation in the printing world and things got mixed up as artists craftsmen and printers found ways to use new materials and processes.

St Gertrude and Her Mice.

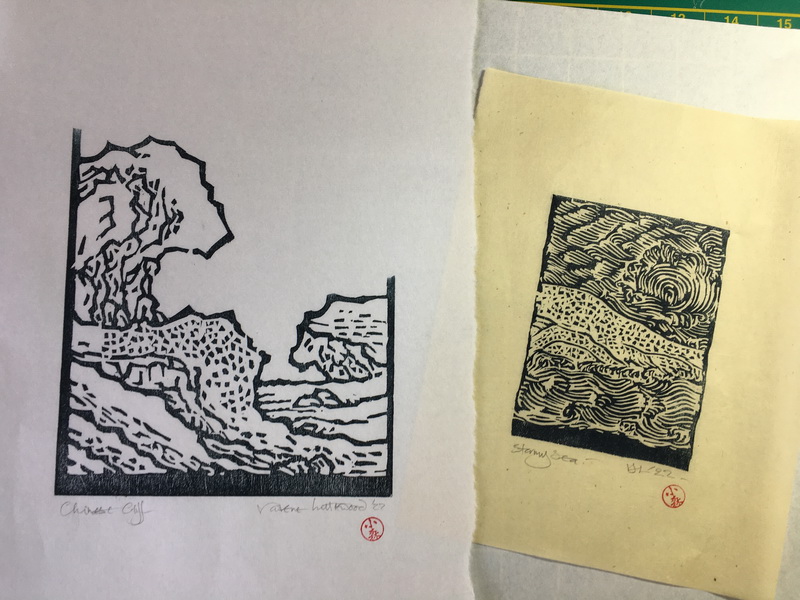

The 17th of March was St Gertrude’s Day and coincidentally while researching the early 15th century I came across a woodcut, thought to be produced in Germany around 1432.

This is from a lovely old book I have, published in 1935 “A History of Woodcut The XV Century: Vol 1 The Primitives, Single Cuts and Block Books” by Arthur M Hind (1880–1957) who was Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum. It’s an old withdrawn library book and still has some uncut pages which I am reluctant to cut. He wrote many books on printmaking and his two volume books on the History of Woodcuts are still available from Dover publications. They are wonderful, very thorough source books. This first volume explores the first part of the 15th century before movable type.

The story of St Gertrude is complex and not entirely clear but legend has it that she was sitting in her monastic cell deeply involved in some spinning. Her concentration was broken by seeing small mice scampering around and looking up, she realised that spring had arrived and went out into the garden. (She is also a patron saint of gardeners). She became the patron saint of the removal of mice and later became associated with cats…in the 1980’s.. how bonkers is that! I don’t think it is entirely holy to be seen with all those mice only to feed them to cats. Honestly I have struggled with this one.

Anyway below are some more lovely images of Gertrude.. I see no cats!

St. Gertrude of Nivelles, German,1440-1450. Inv. 32-1899. Photo: Joerg P. Anders. from The Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen Berlin

A very beautiful painting by Simon Bening. OK not a woodcut but just so lovely I had to include it. It was thought that mice might be the souls of those who had gone to purgatory, so I am not quite sure what is going on with the devil here.

St. Gertrude de Nivelles, from the Hours of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg by Simon Bening Date: c. 1522-1523 from the Carneige Museum of Art. See here

The Buxheim St Christopher

My next inspiration came from the famous early woodcut held in the John Ryland’s Library. It’s one of the earliest dated woodcut prints on paper. Hand coloured, full of life and details. It would have been a welcome print for a traveler to carry with them. A bit of extra protection when travelling, especially to far flung lands with palm trees.

The Buxheim St Christope : image size 288 x 207 mm, woodcut possibly coloured with stencils: John Rylands Library here

![]()

Weekly Woodcut No 10

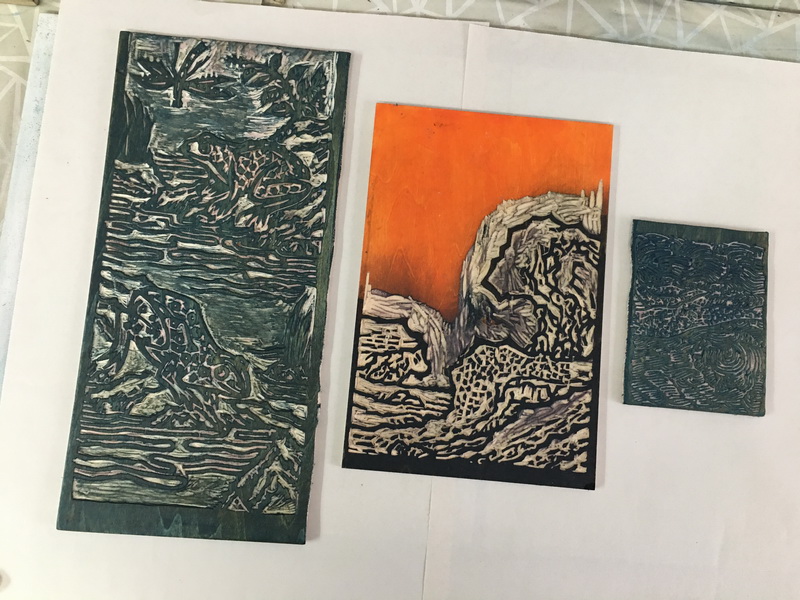

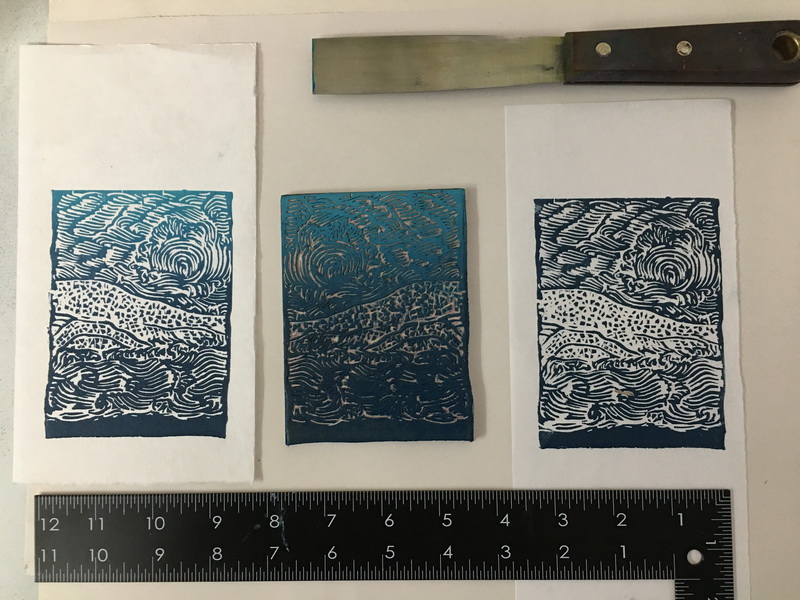

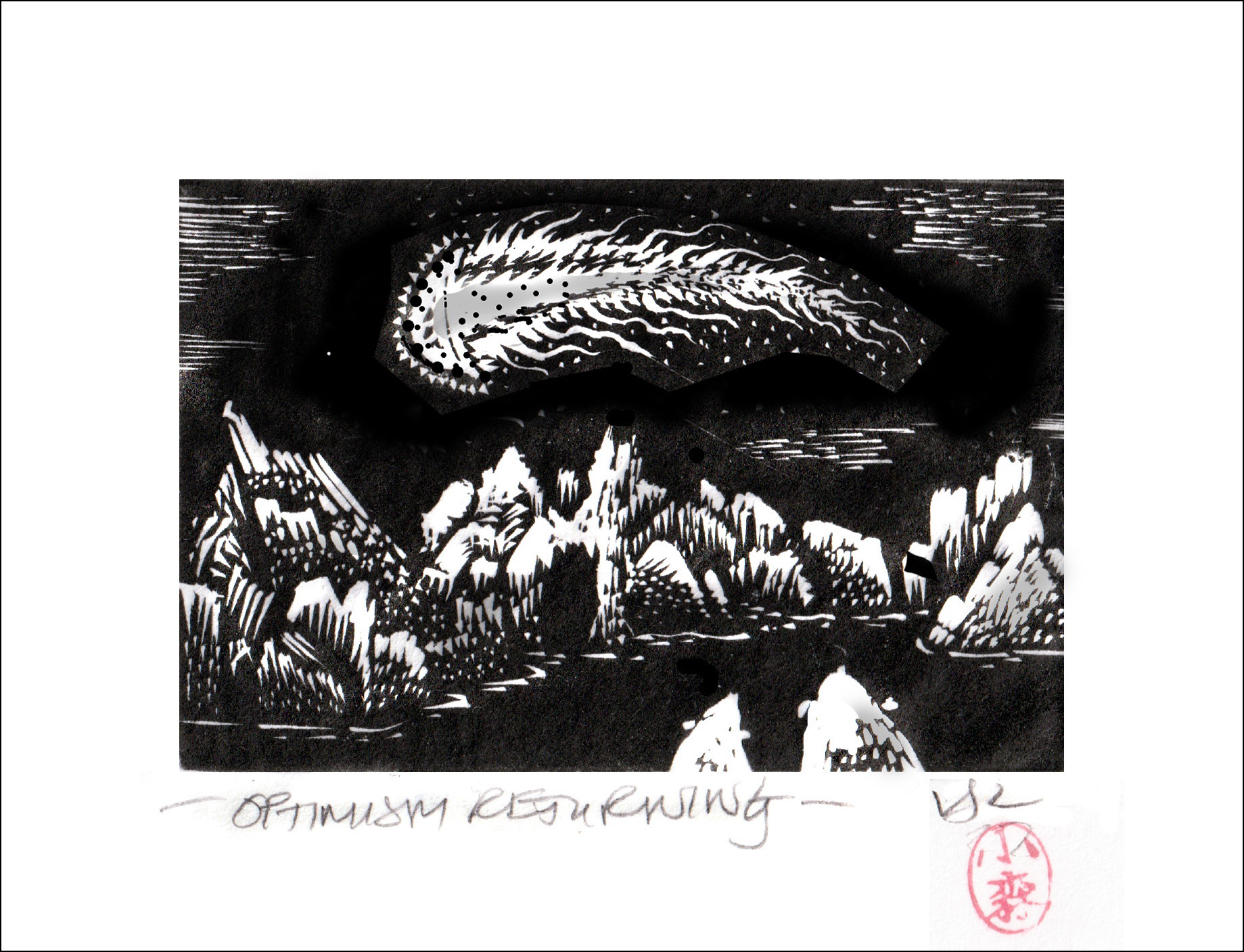

My contributions this week are a bit slight and rushed due to having too much other work and will need a revisit. But I managed some mice and some trees.

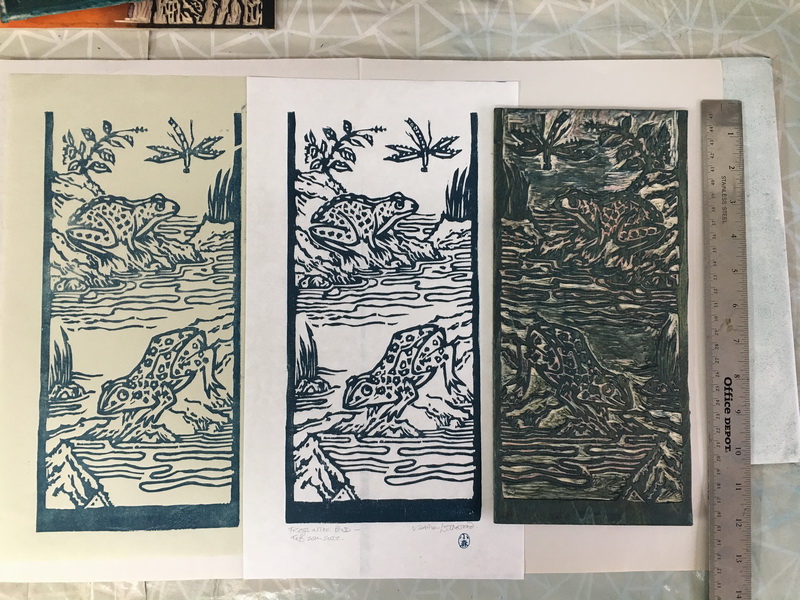

St Gertrude’s Mice

Two mice helping to load the thread onto the spindle.

St Gertrude’s Mice: woodcut in Shina ply; image size 5 x 5 inches.

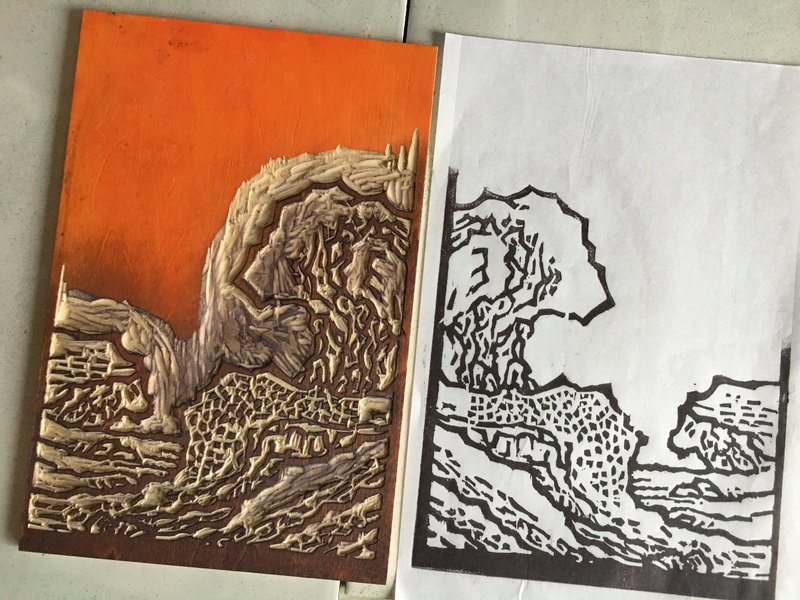

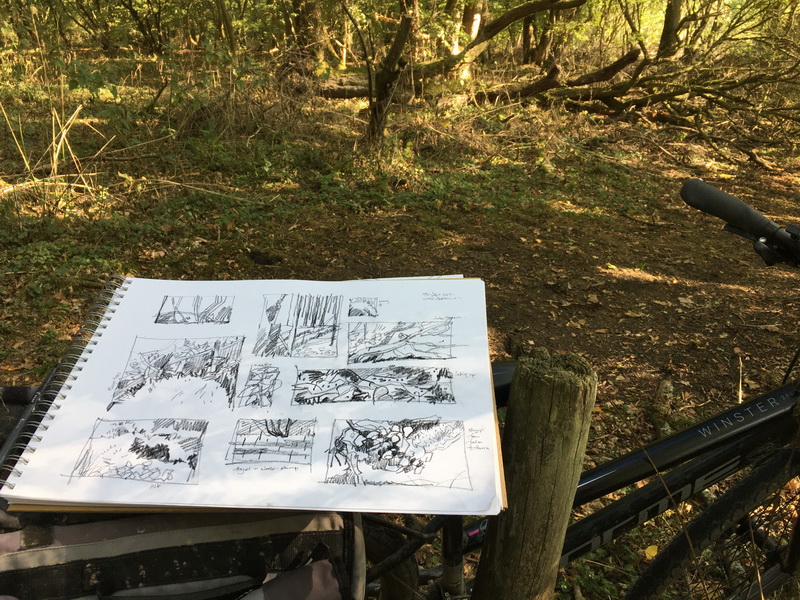

Some Trees

I took parts of the landscape of St Christopher’s print, three trees, the odd little rabbit and St Christopher’s leg just disappearing off to the left. This one was cut on one of the magnolia blocks but I forgot to sand the surface well before working on it, so there were printing ‘issues’. Oh well.. next time.

Block and some trials

St Christopher’s Trees: woodcut; rainbow roll on Heritage book paper; image 6 x 4 inches

While cutting these blocks and sometimes following the lines and shapes of the original, I come to a point where I wonder what the original carver must have thought, about a tricky curve or the choice of a background pattern. I wonder what was important to them, what was proscribed or their choice. Scholars of woodcuts can identify different artist or dates by looking at the cutting style of the folds in cloth.

———————————————-

Having reached woodcut number 10, I am having a short break to catch up with other work. Weekly Woodcut posts will return in a couple of weeks..

Oh! ….and that will be April!